Review: [The Abandoned Miners] (Iwanami Shinsho)

Review: [The Abandoned Miners] (Iwanami Shinsho) by Hidenobu Ueno

I borrowed this book from the library because it was written by Hidenobu Ueno, a mentor of Mr Hiroyuki Miyamatsu, a respected senior member of the Happiness Realization Party when he was a young man.

The first edition of this book was published in 1960, but the book I borrowed from the library was the 13th printing edition in 1971.

I checked the Amazon book reviews and found that the book was in its 23rd printing edition as of 2009 and that it is still being read to this day.

The book has been read for 60 years.

Still, seeing the name of the publisher, Yujiro Iwanami, for the first time in a long while, I felt as if I had seen the light of a bygone era.

As President Ryuho Okawa said in one of his Dharma talks, it was said that scholars in those days were considered to be on their own after publishing a book from Iwanami Shoten, and for scholars, it was a status to have a book published by Iwanami Shoten. (Only a few scholars had books published by Iwanami Shoten.)

It seemed the name Yujiro Iwanami must have shined at that time.

This book, however, has nothing to do with that kind of scholarly status.

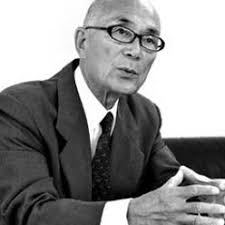

Hidenobu Ueno dropped out of Kyoto University, became a coal miner himself and went underground, while at the same time continuing to record the lives of small and medium-sized mountain coal miners in great detail.

As Mr Ueno himself recalls, the work was like endlessly drawing a living hell, and the endless drawing itself was hell itself, and he himself was fed up with the meaningless work.

However, he said that he was writing about it because there was no one else to record the hellish aspects of the underground, where no light shines. At one point, he said, the media were all over the place reporting on the miners who were unemployed and blowing up.

But that was a temporary boom, and there is no way to read those articles back now.

Sixty years on, there is probably no other way for me to go back and read the facts about the slave labour of small and medium-sized miners, with the exception of Hidenobu Ueno's book. Thus, I can read it because it is in the collection of a local library.

On the internet, second-hand copies of this book fetch high prices - some sell for 9,000 yen. How grateful I am that it is in the library.

Now, I would like to give you a few concrete examples of the slave labour of small and medium-sized mountain miners, from a myriad of examples.

The common facts are that non-payment of wages was a daily occurrence. The system is set up in such a way that they are made to work for free. Powerless miners, without unions, go from one coal mine to another. Unemployed, they sell their blood for food.

Some could not even afford to take a bath. Sometimes they borrowed baths from the big mines, but often the trade unions in the big mines refused to allow the miners in the smaller mines to use the baths. In particular, they were refused by the women's class on the grounds that they would be unclean.

In this sense, they were 'abandoned' even by the major trade unions.

Always next to death. Many cases of people escaping with their lives from mine explosions were also written about.

The most shocking thing to me was that on the morning of the day of a regular government inspection at an illegally operated mine, the miners would enter the illegally stolen mine shaft. Then, when the bureaucrats of the periodic inspection arrive, they explode and bury the entrance to the illegally dug hole.

This is to prevent the officials from discovering the entrance to the mine.

The miners inside are buried alive.

The company's logic is that once the inspection is over, the hole will be dug back up, so they are not killed by being buried alive, and they are told to be patient.

The fear of the miners being buried alive for a certain period of time is unimaginable.

This book is an endless record of such cases.

As a young man, Ueno himself entered the mines and felt righteous indignation at the social structure in which the people abandoned by Japanese society, and those who had been abandoned, supported the bottom line of capitalism.

The kindness shown to Mr Ueno by these abandoned miners, who at first glance appeared to be a bunch of rascals, shone even more brightly because of the 'humanity' shown by these so-called 'animals' who were not treated as human beings. This is why he decided to document these abandoned miners.

In later years, together with photojournalist Hiroyuki Miyamatsu, Ueno travelled to South America, where the miners had emigrated from the mines, and this became his life's work. (I have already written a review of his book on the South American trip.)

The gaze that Mr Ueno devoted to the miners and mine leavers throughout his life has been passed on to Mr Hiroyuki Miyamatsu.

The late Noriaki Tsuchimoto, a world-renowned documentary filmmaker who was born in Toki City next to Mizunami City, Gifu Prefecture, where I live, and whose life's work was to document Minamata disease, once described Mr Miyamatsu as follows.

The author's (Mr Miyamatsu's) eye for detail is astonishingly gentle. I have never known anyone with such infinite love for the weak...".

By reading this book, I have a new understanding of and empathy with the feelings of Mr Tsuchimoto who wrote this. It would not be out of place to read these words as words to Mr Ueno.

I read this book while sitting on the sofa, coffee in hand and listening to classical music.

If the underground abandons and miners in this book could see this figure, they would surely look like aristocrats in some dreamland.

I felt like offering them my infinite gratitude, saying, "These are ordinary Japanese only 60 years later, reaping the benefits of the capitalist development that you have supported from the bottom ground.

Finally, I end my review with a quote from this book.

・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・

A scene in which Mr Ueno is talking to an old miner working in a rehabilitated abandoned mine, p 84.

Mr Ueno: "You are very old, how old are you?"

The old miner remained silent as he continued to slowly add more and more bota (useless coal). It was as if he was recounting his age. Then he finally looked up and murmured.

"Out of this world..."

That was all he could say in reply to my question.

When I asked him about his upbringing, past work history, family and living conditions, he just repeated the same words, without giving me any additional information.

Where is your hometown? After a long silence, he replied, "It's out of this world..."

What about your wages? When I asked him, after a long silence, he simply said, "It's out of this world..." That was all he said.

・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・

Hidenobu Ueno

Hiroyuki Miyamatsu