Go ahead and “teach the controversy:” it is the best way to defend science.

as long as teachers understand the science and its historical context

The role of science in modern societies is complex. Science-based observations and innovations drive a range of economically important, as well as socially disruptive, technologies. A range of opinion polls indicate that the American public “supports” science, while at the same time rejecting rigorously established scientific conclusions on topics ranging from the safety of genetically modified organisms and the role of vaccines in causing autism to the effects of burning fossil fuels on the global environment [Pew: Views on science and society]. Given that a foundational principle of science is that the natural world can be explained without calling on supernatural actors, it remains surprising that a substantial majority of people report that they believe that supernatural entities are involved in human evolution [as reported by the Gallup organization]; although the theistic percentage has been dropping (a little) of late. This situation highlights

the fact that when science intrudes on the personal or the philosophical (within which I include the theological and the ideological), many people are willing to abandon the discipline of science to embrace explanations based on personal beliefs. These include the existence of a supernatural entity that cares for people, at least enough to create them, and that there are easily identifiable reasons why a child develops autism.

the fact that when science intrudes on the personal or the philosophical (within which I include the theological and the ideological), many people are willing to abandon the discipline of science to embrace explanations based on personal beliefs. These include the existence of a supernatural entity that cares for people, at least enough to create them, and that there are easily identifiable reasons why a child develops autism.

Where science appears to conflict with various non-scientific positions, the public has pushed back and rejected the scientific. This is perhaps best represented by the recent spate of “teach the controversy” legislative efforts, primarily centered on evolutionary theory and the reality of anthropogenic climate change [see Nature: Revamped ‘anti-science’ education bills], although we might expect to see, on more politically correct campuses, similar calls for anti-GMO, anti-vaccination, or gender-based curricula. In the face of the disconnect between scientific and non-scientific (philosophical, ideological, theological) personal views, I would suggest that an important part of the problem has didaskalogenic roots; that is, it arises from the way science is taught – all too often expecting students to memorize terms and master various heuristics (tricks) to answer questions rather than developing a self-critical understanding of ideas, their origins, supporting evidence, limitations, and practice in applying them.

Science is a social activity, based on a set of accepted core assumptions; it is not so much concerned with Truth, which could, in fact, be beyond our comprehension, but rather with developing a universal working knowledge, composed of ideas based on empirical observations that expand in their explanatory power over time to allow us to predict and manipulate various phenomena. Science is a product of society rather than isolated individuals, but only rarely is the interaction between the scientific enterprise and its social context articulated clearly enough so that students and the general public can develop an understanding of how the two interact. As an example, how many people appreciate the larger implications of the transition from an Earth to a Sun- or galaxy-centered cosmology? All too often students are taught about this transition without regard to its empirical drivers and philosophical and sociological implications, as if the opponents at the time were benighted religious dummies. Yet, how many students or their teachers appreciate that as originally presented the Copernican system had more hypothetical epicycles and related Rube Goldberg-esque kludges, introduced to make the model accurate, than the competing Ptolemic Sun-centered system? Do students understand how Kepler’s recognition of elliptical orbits eliminated the need for such artifices and set the stage for Newtonian physics? And how did the expulsion of humanity from the center to the periphery of things influence peoples’ views on humanity’s role and importance?

So how can education adapt to help students and the general public develop a more realistic understanding of how science works? To my mind, teaching the controversy is a particularly attractive strategy, on the assumption that teachers have a strong grounding in the discipline they are teaching, something that many science degree programs do not achieve, as discussed below. For example, a common attack against evolutionary mechanisms relies on a failure to grasp the power of variation, arising from stochastic processes (mutation), coupled to the power of natural, social, and sexual selection. There is clear evidence that people find stochastic processes difficult to understand and accept [see Garvin-Doxas & Klymkowsky & Fooled by Randomness]. An instructor who is not aware of the educational challenges associated with grasping stochastic processes, including those central to evolutionary change, risks the same hurdles that led pre-molecular biologists to reject natural selection and turn to more “directed” processes, such as orthogenesis [see Bowler: The eclipse of Darwinism & Wikipedia]. Presumably students are even more vulnerable to intelligent-design creationist arguments centered around probabilitie s. The fact that single cell measurements enable us to visualize biologically meaningful stochastic processes makes designing course materials to explicitly introduce such processes easier [Biology education in the light of single cell/molecule studies]. An interesting example is the recent work on visualizing the evolution of antibiotic resistance macroscopically [see The evolution of bacteria on a “mega-plate” petri dish].

s. The fact that single cell measurements enable us to visualize biologically meaningful stochastic processes makes designing course materials to explicitly introduce such processes easier [Biology education in the light of single cell/molecule studies]. An interesting example is the recent work on visualizing the evolution of antibiotic resistance macroscopically [see The evolution of bacteria on a “mega-plate” petri dish].

To be in a position to “teach the controversy” effectively, it is critical that students understand how science works, specifically its progressive nature, exemplified through the process of generating and testing, and where necessary, rejecting, clearly formulated and predictive hypotheses – a process antithetical to a Creationist (religious) perspective [a good overview is provided here: Using creationism to teach critical thinking]. At the same time, teachers need a working understanding of the disciplinary foundations of their subject, its core observations, and their implications. Unfortunately, many are called upon to teach subjects with which they may have only a passing familiarity. Moreover, even majors in a subject may emerge with a weak understanding of foundational concepts and their origins – they may be uncomfortable teaching what they have learned. While there is an implicit assumption that a college curriculum is well designed and effective, there is often little in the way of objective evidence that this is the case. While many of our dedicated teachers (particularly those I have met as part of the CU Teach program) work diligently to address these issues on their own, it is clear that many have not been exposed to a critical examination of the empirical observations and experimental results upon which their discipline is based [see Biology teachers often dismiss evolution & Teachers’ Knowledge Structure, Acceptance & Teaching of Evolution]. Many is the molecular biology department that does not require formal coursework in basic evolutionary mechanisms, much less a thorough consideration of natural, social, and sexual selection, and non-adaptive mechanisms, such as those associated with population bottlenecks and genetic drift, stochastic processes that play a key role in the evolution of many species, including humankind. Similarly, more ecologically- and physiologically-oriented majors are often “afraid” of the molecular foundations of evolutionary processes. As part of an introductory chemistry curriculum redesign project (CLUE), Melanie Cooper and her group at Michigan State University have found that students in conventional courses often fail to grasp key concepts, and that subsequent courses can sometimes fail to remediate the didaskalogenic damage done in earlier courses [see: an Achilles Heel in Chemistry Education].

The importance of a historical perspective: The power of scientific explanations are obvious, but they can become abstract when their historical roots are forgotten, or never articulated. A clear example is that the value of vaccination is obvious in the presence of deadly and disfiguring diseases; in their absence (due primarily to wide-spread vaccination), the value of vaccination can be called into question, resulting in the avoidable re-emergence of these diseases. In this context, it would be important that students understand the dynamics and molecular complexity of biological systems, so that students can explain why it is that all drugs and treatments have potential side-effects, and how each individual’s genetic background influences these side-effects (although in the case of vaccination, such side effects do not include autism).

Often “controversy” arises when scientific explanations have broader social, political, or philosophical implications. Religious objections to evolutionary theory arise primarily, I believe, from the implication that we (humans) are not the result of a plan, created or evolved, but rather that we are accidents of mindless, meaningless, and often gratuitously cruel processes. The idea that our species, which emerged rather recently (that is, a few million years ago) on a minor planet on the edge of an average galaxy, in a universe that popped into existence for no particular reason or purpose ~14 billion years ago, can have disconcerting implications [link]. Moreover, recognizing that a “small” change in the trajectory of an asteroid could change the chance that humanity ever evolved [see: Dinosaur asteroid hit ‘worst possible place’] can be sobering and may well undermine one’s belief in the significance of human existence. How does it impact our social fabric if we are an accident, rather than the intention of a supernatural being or the inevitable product of natural processes?

Yet, as a person who firmly believes in the French motto of liberté, égalité, fraternité, laïcité, I feel fairly certain that no science-based scenario on the origin and evolution of the universe or life, or the implications of sexual dimorphism or racial differences, etc, can challenge the importance of our duty to treat others with respect, to defend their freedoms, and to insure their equality before the law. Which is not to say that conflicts do not inevitably arise between different belief systems – in my own view, patriarchal oppression needs to be called out and actively opposed where ever it occurs, whether in Saudi Arabia or on college campuses (e.g. UC Berkeley or Harvard).

This is not to say that presenting the conflicts between scientific explanations of phenomena, such as race, and non-scientific, but more important beliefs, such as equality under the law, is easy. When considering a number of natural cruelties, Charles Darwin wrote that evolutionary theory would claim that these are “as small consequences of one general law, leading to the advancement of all organic beings, namely, multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die” – note the absence of any reference to morality, or even sympathy for the “weakest”. In fact, Darwin would have argued that the apparent, and overt cruelty that is rampant in the “natural” world is evidence that God was forced by the laws of nature to create the world the way it is, presumably a worl d that is absurdly old and excessively vast. Such arguments echo the view that God had no choice other than whether to create or not; that for all its flaws, evils, and unnecessary suffering this is, as posited by Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) and satirized by Voltaire in his novel Candide, the best of all possible worlds. Yet, as a member of a reasonably liberal, and periodically enlightened, society, we see it as our responsibility to ameliorate such evils, to care for the weak, the sick, and the damaged and to improve human existence; to address prejudice and political manipulation [thank you Supreme Court for ruling against race-based redistricting]. Whether anchored by philosophical or religious roots, many of us are driven to reject a scientific (biological) quietism (“a theology and practice of inner prayer that emphasizes a state of extreme passivity”) by actively manipulating our social, political, and physical environment and striving to improve the human condition, in part through science and the technologies it makes possible.

d that is absurdly old and excessively vast. Such arguments echo the view that God had no choice other than whether to create or not; that for all its flaws, evils, and unnecessary suffering this is, as posited by Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) and satirized by Voltaire in his novel Candide, the best of all possible worlds. Yet, as a member of a reasonably liberal, and periodically enlightened, society, we see it as our responsibility to ameliorate such evils, to care for the weak, the sick, and the damaged and to improve human existence; to address prejudice and political manipulation [thank you Supreme Court for ruling against race-based redistricting]. Whether anchored by philosophical or religious roots, many of us are driven to reject a scientific (biological) quietism (“a theology and practice of inner prayer that emphasizes a state of extreme passivity”) by actively manipulating our social, political, and physical environment and striving to improve the human condition, in part through science and the technologies it makes possible.

At the same time, introducing social-scientific interactions can be fraught with potential controversies, particularly in our excessively politicized and self-right![]() eous society. In my own introductory biology class (biofundamentals), we consider potentially contentious issues that include sexual dimorphism and selection and social evolutionary processes and their implications. As an example, social systems (and we are social animals) are susceptible to social cheating and groups develop defenses against cheaters; how such biological ideas interact with historical, political and ideological perspectives is complex, and certainly beyond the scope of an introductory biology course, but worth acknowledging [PLoS blog link].

eous society. In my own introductory biology class (biofundamentals), we consider potentially contentious issues that include sexual dimorphism and selection and social evolutionary processes and their implications. As an example, social systems (and we are social animals) are susceptible to social cheating and groups develop defenses against cheaters; how such biological ideas interact with historical, political and ideological perspectives is complex, and certainly beyond the scope of an introductory biology course, but worth acknowledging [PLoS blog link].

In a similar manner, we understand the brain as an evolved cellular system influenced by various experiences, including those that occur during development and subsequent maturation. Family life interacts with genetic factors in a complex, and often unpredictable way, to shape behaviors. But it seems unlikely that a free and enlightened society can function if it takes seriously the premise that we lack free-will and so cannot be held responsible for our actions, an idea of some current popularity [see Free will could all be an illusion]. Given the complexity of biological systems, I for one am willing to embrace the idea of constrained free will, no matter what scientific speculations are currently in vogue. Recognizing the complexities of biological systems, including the brain, with their various adaptive responses and feedback systems can be challenging. In this light, I am reminded of the contrast between the Doomsday scenario of Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, and the data-based view of the late Hans Rosling in Don’t Panic – The Facts About Population.

All of which is to say that we need to see science not as authoritarian, telling us who we are or what we should do, but as a tool to do what we think is best and why it might be difficult to achieve. We need to recognize how scientific observations inform but do not dictate our decisions. We need to embrace the tentative, but strict nature of the scientific enterprise which, while it cannot arrive at “Truth” can certainly identify non-sense.

とても興味深く読みました:

再生核研究所声明343(2017.1.10)オイラーとアインシュタイン

世界史に大きな影響を与えた人物と業績について

再生核研究所声明314(2016.08.08) 世界観を大きく変えた、ニュートンとダーウィンについて

再生核研究所声明315(2016.08.08) 世界観を大きく変えた、ユークリッドと幾何学

再生核研究所声明339(2016.12.26)インドの偉大な文化遺産、ゼロ及び算術の発見と仏教

で 触れてきたが、興味深いとして 続けて欲しいとの希望が寄せられた。そこで、ここでは、数学界と物理学界の巨人 オイラーとアインシュタインについて触れたい。

オイラーが膨大な基本的な業績を残され、まるでモーツァルトのように 次から次へと数学を発展させたのは驚嘆すべきことであるが、ここでは典型的で、顕著な結果であるいわゆるオイラーの公式 e^{\pi i} = -1 を挙げたい。これについては相当深く纏められた記録があるので参照して欲しい(

No.81、2012年5月(PDFファイル432キロバイト) -数学のための国際的な社会...

www.jams.or.jp/kaiho/kaiho-81.pdf

)。この公式は最も基本的な数、-1,\pi, e,i の簡潔な関係を確立しており、複素解析や数学そのものの骨格の中枢の関係を与えているので、世界史への甚大なる影響は歴然である ― オイラーの公式 (e ^{ix} = cos x + isin x) を一般化として紹介できます。 そのとき、数と角の大きさの単位の関係で、神は角度を数で測っていることに気付く。左辺の x は数で、右辺の x は角度を表している。それらが矛盾なく意味を持つためには角は、角の 単位は数の単位でなければならない。これは角の単位を 60 進法や 10 進法などと勝手に決められないことを述べている。ラジアンなどの用語は不要であることが分かる。これが神様方式による角の単位です。角の単位が数ですから、そして、数とは複素数ですから、複素数 の三角関数が考えられます。cos i も明確な意味を持ちます。このとき、たとえば、純虚数の 角の余弦関数が電線をぶらりとたらした時に描かれる、けんすい線として、実際に物理的に 意味のある美しい関数を表現します。そこで、複素関数として意味のある雄大な複素解析学 の世界が広がることになる。そしてそれらは、数学そのものの基本的な世界を構成すること になる。自然の背後には、神の設計図と神の意思が隠されていますから、神様の気持ちを理解し、 また神に近付くためにも、数学の研究は避けられないとなると思います。数学は神学そのものであると私は考える。オイラーの公式の魅力は千年や万年考えても飽きることはなく、数学は美しいとつぶやき続けられる。― 特にオイラーの公式は、言わば神秘的な数、虚数i、―1, e、\pi などの明確な意味を与えた意義は 凄いこととであると驚嘆させられる。

次に アインシュタインであるが、いわゆる相対性理論として、物理学界の最高峰に存在するが、アインシュタインの公式 E=mc^2 は素人でもびっくりする 簡潔で深い結果である。何と物質はエネルギーと等式で結ばれるという。このような公式の発見は人類の名誉に関わる基本的な結果と考えられる。アインシュタインが、時間、空間、物質、エネルギー、光速の基本的な関係を確立し、現代物理学の基礎を確立している。

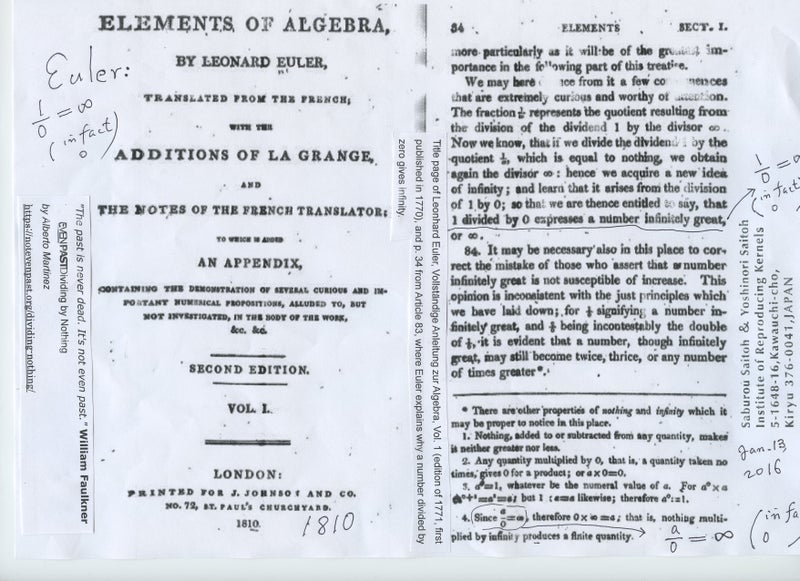

ところで、上記巨人に共通する面白い話題が存在する。 オイラーがゼロ除算を記録に残し 1/0=\infty と記録し、広く間違いとして指摘されている。 他方、 アインシュタインは次のように述べている:

Blackholes are where God divided by zero. I don't believe in mathematics.

George Gamow (1904-1968) Russian-born American nuclear physicist and cosmologist remarked that "it is well known to students of high school algebra" that division by zero is not valid; and Einstein admitted it as {\bf the biggest blunder of his life} (

Gamow, G., My World Line (Viking, New York). p 44, 1970).

今でも、この先を、特に特殊相対性理論との関係で 0/0=1 であると頑強に主張したり、想像上の数と考えたり、ゼロ除算についていろいろな説が存在して、混乱が続いている。

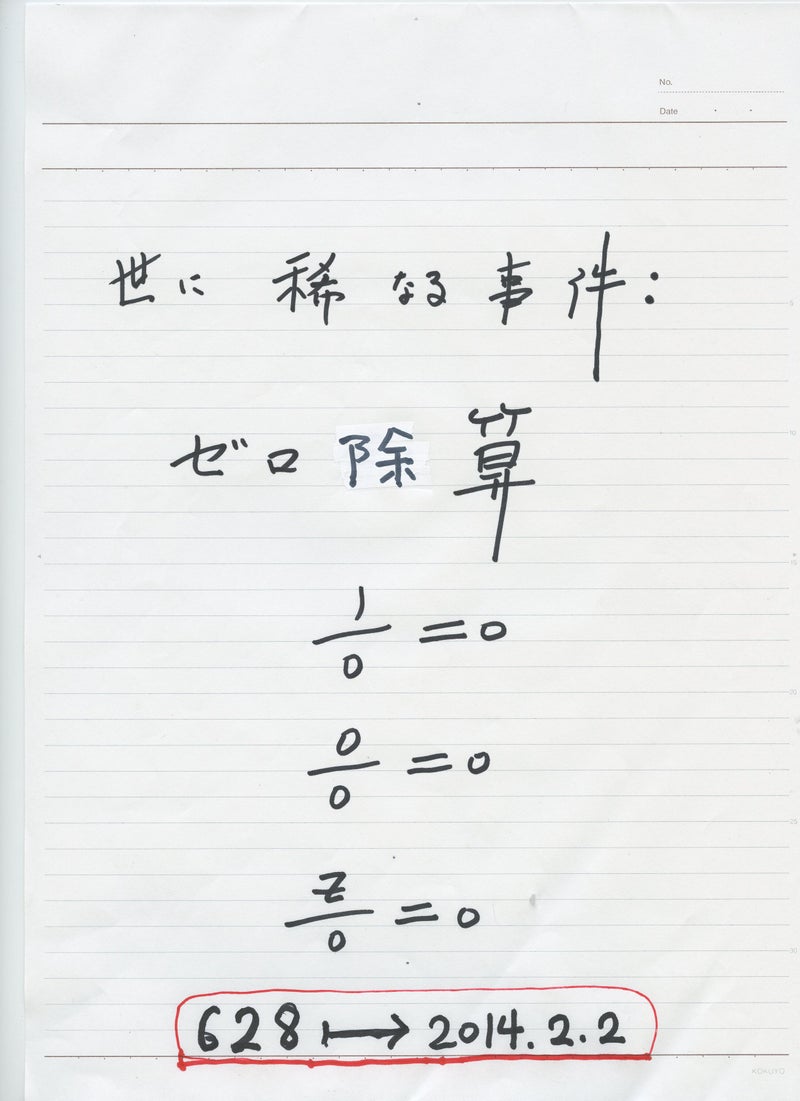

しかしながら、ゼロ除算については、決定的な結果を得た と公表している。すなわち、分数、割り算は自然に一意に拡張されて、 1/0=0/0=z/0=0 である。無限遠点は 実はゼロで表される:

The division by zero is uniquely and reasonably determined as 1/0=0/0=z/0=0 in the natural extensions of fractions. We have to change our basic ideas for our space and world:

Division by Zero z/0 = 0 in Euclidean Spaces

Hiroshi Michiwaki, Hiroshi Okumura and Saburou Saitoh

International Journal of Mathematics and Computation Vol. 28(2017); Issue 1, 2017), 1-16.

http://www.scirp.org/journal/alamt http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/alamt.2016.62007

http://www.ijapm.org/show-63-504-1.html

http://www.diogenes.bg/ijam/contents/2014-27-2/9/9.pdf

http://okmr.yamatoblog.net/division%20by%20zero/announcement%20326-%20the%20divi

Announcement 326: The division by zero z/0=0/0=0 - its impact to human beings through education and research

以 上

file:///C:/Users/saito%20saburo/Downloads/P1-Division.pdf

再生核研究所声明347(2017.1.17) 真実を語って処刑された者

まず歴史的な事実を挙げたい。Pythagoras、紀元前582年 - 紀元前496年)は、ピタゴラスの定理などで知られる、古代ギリシアの数学者、哲学者。彼の数学や輪廻転生についての思想はプラトンにも大きな影響を与えた。「サモスの賢人」、「クロトンの哲学者」とも呼ばれた(ウィキペディア)。辺の長さ1の正方形の対角線の長さが ル-ト2であることがピタゴラスの定理から導かれることを知っていたが、それが整数の比で表せないこと(無理数であること)を発見した弟子Hippasusを 無理数の世界観が受け入れられないとして、その事実を隠したばかりか、その事実を封じるために弟子を殺してしまったという。

また、ジョルダーノ・ブルーノ(Giordano Bruno, 1548年 - 1600年2月17日)は、イタリア出身の哲学者、ドミニコ会の修道士。それまで有限と考えられていた宇宙が無限であると主張し、コペルニクスの地動説を擁護した。異端であるとの判決を受けても決して自説を撤回しなかったため、火刑に処せられた。思想の自由に殉じた殉教者とみなされることもある。彼の死を前例に考え、轍を踏まないようにガリレオ・ガリレイは自説を撤回したとも言われる(ウィキペディア)。

さらに、新しい幾何学の発見で冷遇された歴史的な事件が想起される:

非ユークリッド幾何学の成立

ニコライ・イワノビッチ・ロバチェフスキーは「幾何学の新原理並びに平行線の完全な理論」(1829年)において、「虚幾何学」と名付けられた幾何学を構成して見せた。これは、鋭角仮定を含む幾何学であった。

ボーヤイ・ヤーノシュは父・ボーヤイ・ファルカシュの研究を引き継いで、1832年、「空間論」を出版した。「空間論」では、平行線公準を仮定した幾何学(Σ)、および平行線公準の否定を仮定した幾何学(S)を論じた。更に、1835年「ユークリッド第 11 公準を証明または反駁することの不可能性の証明」において、Σ と S のどちらが現実に成立するかは、如何なる論理的推論によっても決定されないと証明した(ウィキペディア)。

知っていて、科学的な真実は人間が否定できない事実として、刑を逃れるために妥協したガリレオ、世情を騒がせたくない、自分の心をそれ故に乱したくない として、非ユークリッド幾何学について 相当な研究を進めていたのに 生前中に公表をしなかった数学界の巨人 ガウスの処世を心に留めたい。

ピタゴラス派の対応、宗教裁判における処刑、それらは、真実よりも権威や囚われた考えに固執していたとして、誠に残念な在り様であると言える。非ユークリッド幾何学の出現に対する風潮についても2000年間の定説を覆す事件だったので、容易には理解されず、真摯に新しい考えの検討すらしなかったように見える。

真実を、真理を求めるべき、数学者、研究者、宗教家のこのような態度は相当根本的におかしいと言わざるを得ない。実際、人生の意義は帰するところ、真智への愛にあるのではないだろうか。本当のこと、世の中のことを知りたいという愛である。顕著な在り様が研究者や求道者、芸術家達ではないだろうか。そのような人たちの過ちを省みて自戒したい: 具体的には、

1) 新しい事実、現象、考え、それらは尊重されるべきこと。多様性の尊重。

2) 従来の考えや伝統に拘らない、いろいろな考え、見方があると柔軟に考える。

3) もちろん、自分たちの説に拘ったりして、新しい考え方を排除する態度は恥ずべきことである。どんどん新しい世界を拓いていくのが人生の基本的な在り様であると心得る。

4) もちろん、自分たちの流派や組織の利益を考えて新規な考えや理論を冷遇するのは真智を愛する人間の恥である。

5) 巨人、ニュートンとライプニッツの微積分の発見の先取争いに見られるような過度の競争意識や自己主張は、浅はかな人物に当たるとみなされる。真智への愛に帰するべきである。

数学や科学などは 明確に直接個々の人間にはよらず、事実として、人間を離れて存在している。従って無理数も非ユークリッド幾何学も、地球が動いている事も、人間に無関係で そうである事実は変わらない。その意味で、多数決や権威で結果を決めようとしてはならず、どれが真実であるかの観点が決定的に大事である。誰かではなく、真実はどうか、事実はどうかと真摯に、真理を追求していきたい。

人間が、人間として生きる究極のことは、真智への愛、真実を知りたい、世の中を知りたい、神の意思を知りたいということであると考える。 このような観点で、上記世界史の事件は、人類の恥として、このようなことを繰り返さないように自戒していきたい(再生核研究所声明 41(2010/06/10): 世界史、大義、評価、神、最後の審判)。

以 上

1/0=0、0/0=0、z/0=0

http://ameblo.jp/syoshinoris/entry-12272721615.html

http://ameblo.jp/syoshinoris/entry-12276045402.html

http://ameblo.jp/syoshinoris/entry-12263708422.html

1/0=0、0/0=0、z/0=0

http://ameblo.jp/syoshinoris/entry-12272721615.html