Color blindness (or color vision deficiency) is the name given to the condition where people find it difficult to identify or distinguish different colors. An Ishihara test is a common way to test for certain types of color blindness , and here we'll talk you through how this simple test works.

What is the Ishihara color blindness test?

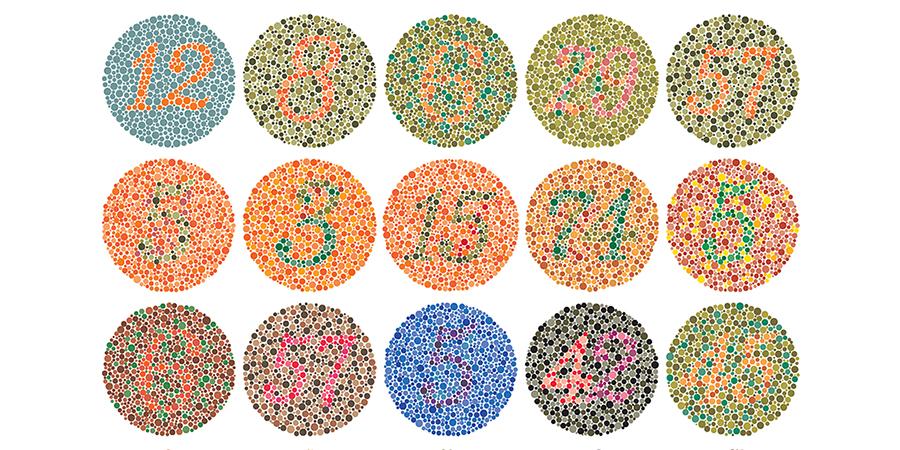

The Ishihara test was developed in 1917 by Japanese ophthalmologist, Shinobu Ishihara . It's become one of the most common ways to test for red and green color deficiencies, particularly in children. The test involves identifying colored numbers or shapes contained within a series of differently colored dots.

Other common color vision tests involve color arrangement in which you're asked to arrange colors in order of their shade or to identify matching colors. The City University Test (developed by City University London) and the Farnsworth D-15 test are examples. can be more useful in detecting blue light deficiencies, which the Ishihara test doesn't cover.

How does the Ishihara test work?

You'll easily recognize an Ishihara test – it's quite a common test in children's eye tests where these types of color deficiencies can be picked up.

Your optician will have a book made up of 38 different plates, known as pseudoisochromatic plates. Each plate features a circle formed by a range of dots in different colors and sizes. Within each circle, there are a series of dots in a different color that Usually make up the shape of a number (for small children these might be other shapes that they can easily identify).

They will show you a range of these plates and ask you what number you can see for each one. Colors that may at first seem equal (or'iso') to your brain, but are actually different, are shown to you together – it's People with normal color vision are able to work out the false (or'pseudo') similarity between the two colors and see the hidden number with no problem. If you find it difficult to tell what the number is on certain plates, then it can indicate a color vision deficiency.

If you have difficulty seeing the numbers on a certain amount of plates, your optician will be able to make a diagnosis of color blindness.

What are the most common forms of color blindness?

The Ishihara test is used to detect the most common types of color blindness, which are categorized as red-green color deficiencies (known as protanomaly and deuteranomaly).

This is a general term that covers a range of types and severities, but in general means that people are unable to see or differentiate colors that have red or green as part of the whole colors. So for example, people with a red deficiency will find it difficult to see the difference between blue and purple because they are unable to detect the red properties of purple.

Your optician might carry out a color arrangement test too, to confirm the results from the Ishihara test, as well as testing for the blue-light deficiency (tritanomaly), which an Ishihara test doesn't test for.

Who should have an Ishihara test?

It's likely that red-green color deficiency would be picked up during childhood, and opticians may include an Ishihara test during a children's eye test to spot this early. But color blindness can happen at any age and can often develop as a result of certain health conditions, like diabetes and multiple sclerosis, or as a consequence of the eye disease glaucoma. Medications or exposure to certain chemicals can also cause color deficiencies. So if you notice any changes in your color vision, you should see your optician who can check this for you.

Color vision tests aren't part of our usual eye tests, so just let us know if you'd like one.

Are online color blindness tests reliable?

There are some online tests around that can give an indication of a possible problem with your colour vision, but they're not always very reliable because the display settings on your screen can differ quite a bit. an optician.

What are the different types of color blindness?

There are seven official diagnoses of color blindness: four different types of color blindness fall in the red-green category, two are in the blue-yellow spectrum and one version describes a type of vision completely lacking in color.

To understand the multiple types of color blindness that exist, it can be helpful to briefly review the basic mechanisms of human vision. Our eyeballs have two kinds of photoreceptors in the retina that are designed to absorb light. Named after their shapes, they are called rods and cones.

Rods are highly sensitive. They are the reason your eyes will adjust in a dark room, allowing you to see basic shapes. The human eye has eighteen times more rods than cones. But the cones are what give us fine detail and color. best in bright daylight. All types of color blindness have to do with diminished (or absent) functionality in the cones.

The human eye contains three different types of cones. S-cones (short-wavelength absorbing cones) help us see blue, M-cones (medium-wavelength absorbing cones) reveal green and L-cones (long-wavelength cones) interpret red light The absence of any of the three types of cones is what accounts for different types of color blindness.

With just those three light sensitivities, we can see literally thousands of colors. Individuals who have all three types of cones working at full capacity are called trichromats (tri meaning three and chroma being the Greek word for color). Similarly, normal vision can be referred to as trichromacy.

The different types of color blindness are generally divided by whether the vision defect is inherited or acquired. Inherited types of color blindness are grouped by red-green and blue-yellow, along with the more rare monochromacy (total color blindness).

Similar distinctions exist among the acquired forms of color blindness. Though the causes may be different, the resulting symptoms (color blindness of some degree of severity) are ultimately caused by deficiencies in the cone photoreceptors.